The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) and other Machine Learning tools such as CLIP and semantic search has made Vector Databases a critical component of modern infrastructure. But unlike traditional databases that search for exact substring matches, vector databases search for meaning.

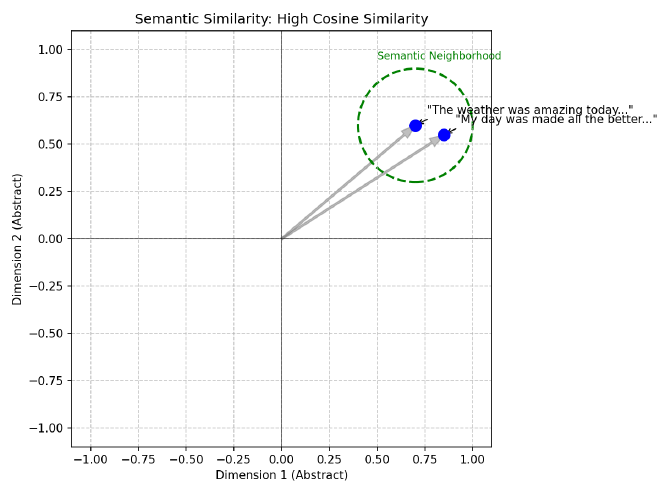

For example, if we vectorize two separate images of a dog in some representation space, we should expect that those vectors should be closer together than the vectors of an image of a dog to that of an image of a car. Similarly, these two sentences should be expected to be closer together because they have similar meaning:

The weather was amazing today and made me so happy!

My day was made all the better by the beautiful weather!

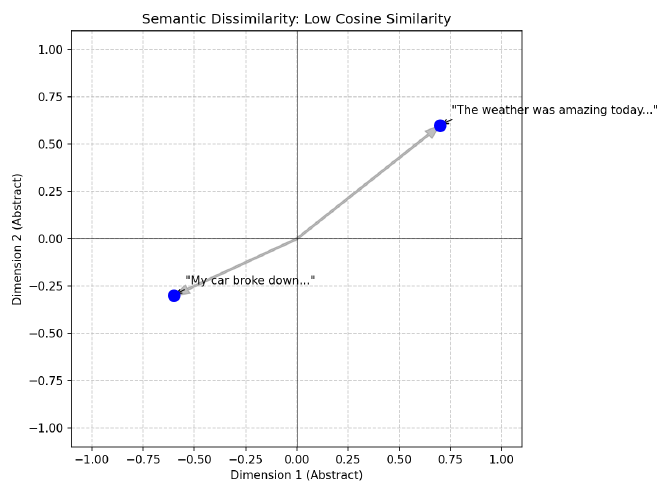

And we should also expect these two sentences to have vector representations that are much further away from each other because their meanings are quite different:

The weather was amazing today and made me so happy!

My car broke down and I got a flat tire on the way to work!

Intuitively this makes sense, but intuition isn’t good enough for computation. So how do we quantify these differences in a scalable, efficient manner?

To do this, we rely on Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) algorithms to navigate high-dimensional spaces efficiently. This post provides an introduction to the core algorithms that empower embedding vector searching at scale.

1.1 The Classical Approach: Space Partitioning#

Before we had modern vector databases, we had spatial indexes. In low-dimensional spaces (like 2D maps or 3D CAD models), we solved the nearest neighbor problem using Space Partitioning Trees:

KD-Trees (k-dimensional Trees)#

A KD-Tree is a binary tree that splits the data space into two halves at every node using axis-aligned hyperplanes (hyperplanes are just n-dimensional planes).

- Root: Split the data along the X-axis (dimension 0) at the median. Points with $x < median$ go left; points with $x \ge median$ go right.

- Level 1: Split each child node along the Y-axis (dimension 1). Notice in the diagram below that the split values (e.g., $Y < 30$ vs $Y < 80$) are different for each branch because they are the local medians for that specific subset of points.

- Level 2: Split along the Z-axis (dimension 2), and so on, cycling through dimensions.

class Node:

def __init__(self, point, left=None, right=None, axis=0):

self.point = point

self.left = left

self.right = right

self.axis = axis

def build_kdtree(points, depth=0):

if not points:

return None

k = len(points[0]) # dimensionality

axis = depth % k # cycle through axes

# Sort points and choose median

points.sort(key=lambda x: x[axis])

median = len(points) // 2

return Node(

point=points[median],

left=build_kdtree(points[:median], depth + 1),

right=build_kdtree(points[median + 1:], depth + 1),

axis=axis

)

type Node struct {

Point []float64

Left *Node

Right *Node

Axis int

}

func BuildKDTree(points [][]float64, depth int) *Node {

if len(points) == 0 {

return nil

}

k := len(points[0])

axis := depth % k

// Sort by current axis (simplified)

sort.Slice(points, func(i, j int) bool {

return points[i][axis] < points[j][axis]

})

median := len(points) / 2

return &Node{

Point: points[median],

Left: BuildKDTree(points[:median], depth+1),

Right: BuildKDTree(points[median+1:], depth+1),

Axis: axis,

}

}

struct Node {

std::vector<double> point;

Node *left = nullptr;

Node *right = nullptr;

int axis;

Node(std::vector<double> pt, int ax) : point(pt), axis(ax) {}

};

Node* buildKDTree(std::vector<std::vector<double>>& points, int depth) {

if (points.empty()) return nullptr;

int axis = depth % points[0].size();

int median = points.size() / 2;

// Use nth_element to find median in O(N)

std::nth_element(points.begin(), points.begin() + median, points.end(),

[axis](const auto& a, const auto& b) { return a[axis] < b[axis]; });

Node* node = new Node(points[median], axis);

std::vector<std::vector<double>> leftPoints(points.begin(), points.begin() + median);

std::vector<std::vector<double>> rightPoints(points.begin() + median + 1, points.end());

node->left = buildKDTree(leftPoints, depth + 1);

node->right = buildKDTree(rightPoints, depth + 1);

return node;

}

Search: To find the nearest neighbor, you traverse the tree from root to leaf ($\log N$ steps). You can prune entire branches of the tree if the query point is too far from the bounding box of that branch. In low dimensions ($d < 10$), this is incredibly efficient.

R-Trees: Object-Centric Grouping#

While KD-Trees partition the space (splitting the canvas like a grid, regardless of where the data is), R-Trees partition the data (grouping the ink, drawing boxes only where the points actually exist).

The Core Concept: Minimum Bounding Rectangles (MBRs) An R-Tree groups nearby objects into a box described by its coordinates: $(min_x, min_y)$ and $(max_x, max_y)$.

- Leaf Nodes: Contain actual data points.

- Internal Nodes: Contain the “MBR” that encompasses all its children.

The Fatal Flaw: Overlap Unlike KD-Trees, where a point belongs strictly to the Left or Right side of a split, R-Tree nodes can overlap. A single query point might fall inside the bounding boxes of multiple sibling nodes.

- Low Dimensions: Overlap is minimal; search remains $O(\log N)$.

- High Dimensions: As dimensions rise, the “empty space” problem forces MBRs to grow larger to encompass their children. Eventually, MBRs overlap significantly. A single query might intersect with 50% of the tree’s branches, destroying the pruning advantage.

Search Logic: You calculate which MBRs intersect with your query’s search radius. You must descend into every intersecting MBR.

class MBR:

def __init__(self, min_coords, max_coords):

self.min = min_coords # [x_min, y_min, ...]

self.max = max_coords # [x_max, y_max, ...]

def intersects(self, query_point, radius):

# Accumulate squared distances across ALL dimensions

dist_sq = 0

for i in range(len(query_point)):

# Per-dimension distance to the box

delta = 0

if query_point[i] < self.min[i]:

delta = self.min[i] - query_point[i]

elif query_point[i] > self.max[i]:

delta = query_point[i] - self.max[i]

dist_sq += delta * delta

return dist_sq <= radius * radius

type MBR struct {

Min []float64

Max []float64

}

func (m MBR) Intersects(query []float64, radius float64) bool {

distSq := 0.0

for i := range query {

delta := 0.0

if query[i] < m.Min[i] {

delta = m.Min[i] - query[i]

} else if query[i] > m.Max[i] {

delta = query[i] - m.Max[i]

}

distSq += delta * delta

}

return distSq <= radius*radius

}

struct MBR {

std::vector<double> min_coords;

std::vector<double> max_coords;

bool intersects(const std::vector<double>& query, double radius) {

double dist_sq = 0.0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < query.size(); ++i) {

double delta = 0.0;

if (query[i] < min_coords[i]) {

delta = min_coords[i] - query[i];

} else if (query[i] > max_coords[i]) {

delta = query[i] - max_coords[i];

}

dist_sq += delta * delta;

}

return dist_sq <= radius * radius;

}

};

The Failure Mode: Why Pruning Fails in High Dimensions#

What is Pruning? In a search tree, “pruning” means safely ignoring an entire branch of the tree. If you know for a fact that the closest point in a branch is 10 units away, but you’ve already found a neighbor that is 5 units away, you don’t need to enter that branch at all. You “prune” it. This is what gives trees their $O(\log N)$ speed—you skip most of the data since it isn’t relevant to your search.

The “High-Dimensional” Problem In 2D or 3D, space is “crowded” and data points are distinct. If you are in one quadrant, you are far from the others. However, as dimensions increase ($d > 10$), a strange geometric phenomenon occurs: points move to the edges [5].

Imagine a high-dimensional hypercube. The volume of the cube is $1^d$. The volume of a slightly smaller inscribed cube (say, 90% size) is $0.9^d$.

- In 2D: $0.9^2 = 0.81$ (81% of volume is in the center).

- In 100D: $0.9^{100} \approx 0.00002$ (Almost 0% of volume is in the center!).

The Consequence: Almost all data points sit on the “surface” or shell of the structure. When you query this space:

- Your query point is almost always near a “boundary” of the partition.

- The “search radius” effectively overlaps with every partition.

- You cannot prove that a branch is “too far away” because in high dimensions, everything is roughly equidistant to everything else (relative to the vastness of the space).

Because you can’t rule out any branches, you are forced to visit them all. The tree devolves into a complicated, slow linked list, often performing worse than a brute-force linear scan.

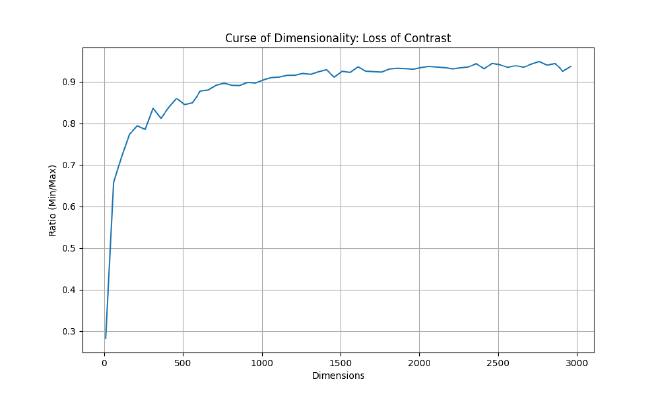

1.2 The Challenge: The Curse of Dimensionality#

Before diving into the solutions, we must understand the problem. Why can’t we just use a B-Tree or a KD-Tree?

In low-dimensional spaces (like 2D or 3D geographical data), structures like KD-Trees or R-Trees work beautifully. They partition space so you can quickly discard vast regions that are “too far away.”

However, modern embedding models (like CLIP or OpenAI’s text-embedding-3) output vectors with hundreds or thousands of dimensions (e.g., 512, 768, 1536, or 3072). In these high-dimensional spaces, a phenomenon known as the Curse of Dimensionality renders traditional spatial partitioning ineffective.

Mathematically, as dimension $d$ increases:

- Distance Concentration [5]: The ratio of the distance to the nearest neighbor vs. the farthest neighbor approaches 1. The relative contrast between “close” and “far” vanishes. In other words, everything becomes roughly equidistant to everything else, making it impossible for the algorithm to distinguish a “clear” winner.

- Empty Space: As discussed in the Failure Mode section above, volume expands exponentially, pushing all data points to the surface.

The “Dice Roll” Intuition: Think of 1 dimension as rolling a single die. You can easily get a 1 (min) or a 6 (max). The “contrast” is high. Now, think of 1,000 dimensions as summing 1,000 independent dice. According to the Central Limit Theorem, the sum of independent random variables tends toward a Normal Distribution (Gaussian). The result will cluster tightly around the mean (3,500). It is effectively statistically impossible to roll all 1s (1,000) or all 6s (6,000). In high dimensions, every vector is effectively a “sum of many dice.” Its length (norm) and distance to others converge to a statistical mean. The “spikes” (unique features) get washed out in the law of large numbers.

To visualize this, here is a script to generate the “Ratio of Distances” graph shown above.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def calculate_ratio(dim, num_points=1000):

# Generate random points on unit sphere

points = np.random.randn(num_points, dim)

points /= np.linalg.norm(points, axis=1)[:, np.newaxis]

# Calculate min/max pairwise distances

# (Approximation: compare 1st point to all others to save time)

diff = points[1:] - points[0]

dists = np.linalg.norm(diff, axis=1)

return np.min(dists) / np.max(dists)

dims = range(10, 3000, 50)

ratios = [calculate_ratio(d) for d in dims]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(dims, ratios, label='Min/Max Distance Ratio')

plt.xlabel('Dimensions')

plt.ylabel('Ratio (Min/Max)')

plt.title('Curse of Dimensionality: Loss of Contrast')

plt.grid(True)

plt.savefig('curse_of_dimensionality.png')

print("Graph saved to curse_of_dimensionality.png")

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

"math/rand"

)

func calculateRatio(dim, numPoints int) float64 {

points := make([][]float64, numPoints)

for i := range points {

points[i] = make([]float64, dim)

var norm float64

for j := 0; j < dim; j++ {

v := rand.NormFloat64()

points[i][j] = v

norm += v * v

}

norm = math.Sqrt(norm)

for j := 0; j < dim; j++ {

points[i][j] /= norm

}

}

minDist, maxDist := math.MaxFloat64, 0.0

// Compare point 0 to all others

for i := 1; i < numPoints; i++ {

var distSq float64

for k := 0; k < dim; k++ {

diff := points[0][k] - points[i][k]

distSq += diff * diff

}

dist := math.Sqrt(distSq)

if dist < minDist { minDist = dist }

if dist > maxDist { maxDist = dist }

}

return minDist / maxDist

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("dimension,ratio")

for dim := 10; dim <= 3000; dim += 50 {

ratio := calculateRatio(dim, 1000)

fmt.Printf("%d,%.4f\n", dim, ratio)

}

// Pipe this output to a plotting tool

}

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <random>

#include <cmath>

#include <algorithm>

#include <iomanip>

double calculate_ratio(int dim, int num_points = 1000) {

std::vector<std::vector<double>> points(num_points, std::vector<double>(dim));

std::mt19937 gen(42);

std::normal_distribution<> d(0, 1);

for (int i = 0; i < num_points; ++i) {

double norm_sq = 0.0;

for (int j = 0; j < dim; ++j) {

points[i][j] = d(gen);

norm_sq += points[i][j] * points[i][j];

}

double norm = std::sqrt(norm_sq);

for (int j = 0; j < dim; ++j) {

points[i][j] /= norm;

}

}

double min_dist = 1e9;

double max_dist = 0.0;

// Compare point 0 to all others

for (int i = 1; i < num_points; ++i) {

double dist_sq = 0.0;

for (int k = 0; k < dim; ++k) {

double diff = points[0][k] - points[i][k];

dist_sq += diff * diff;

}

double dist = std::sqrt(dist_sq);

min_dist = std::min(min_dist, dist);

max_dist = std::max(max_dist, dist);

}

return min_dist / max_dist;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "dimension,ratio\n";

for (int dim = 10; dim <= 3000; dim += 50) {

double ratio = calculate_ratio(dim);

std::cout << dim << "," << std::fixed << std::setprecision(4) << ratio << "\n";

}

// Pipe this output to a plotting tool

return 0;

}

This forces us to compromise: we trade exactness for speed, accepting “approximate” nearest neighbors (ANN) to achieve sub-linear search times.

2. Distance Metrics: The Foundation#

1.3 Baseline: Linear Search (Exact k-NN)#

Before optimizing, it’s useful to know the baseline. This is the $O(N)$ approach.

import numpy as np

def linear_search(query, dataset):

best_dist = float('inf')

best_item = None

for item in dataset:

dist = np.linalg.norm(query - item)

if dist < best_dist:

best_dist = dist

best_item = item

return best_item, best_dist

func LinearSearch(query []float64, dataset [][]float64) ([]float64, float64) {

bestDist := math.MaxFloat64

var bestItem []float64

for _, item := range dataset {

dist := EuclideanDistance(query, item)

if dist < bestDist {

bestDist = dist

bestItem = item

}

}

return bestItem, bestDist

}

#include <vector>

#include <limits>

#include <cmath>

std::pair<std::vector<double>, double> linear_search(const std::vector<double>& query, const std::vector<std::vector<double>>& dataset) {

double best_dist = std::numeric_limits<double>::max();

std::vector<double> best_item;

for (const auto& item : dataset) {

double dist = euclidean_distance(query, item);

if (dist < best_dist) {

best_dist = dist;

best_item = item;

}

}

return {best_item, best_dist};

}

All ANN algorithms operate on a distance (or similarity) function between vectors. The choice of metric affects both the mathematics of the index and the quality of retrieval results.

Euclidean Distance (L2)#

Measures the straight-line distance between two points in $\mathbb{R}^d$:

$$d_{\text{L2}}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{d} (x_i - y_i)^2}$$

Cosine Similarity#

Measures the angle between two vectors, normalized to [-1, 1]. It effectively ignores the magnitude of the vectors, focusing only on their direction (semantic meaning).

$$\text{cos}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \frac{\mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{y}}{|\mathbf{x}| \cdot |\mathbf{y}|} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{d} x_i y_i}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{d} x_i^2} \cdot \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{d} y_i^2}}$$

Inner Product (IP / Dot Product)#

Used when vectors are pre-normalized:

$$\text{IP}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \sum_{i=1}^{d} x_i y_i$$

import numpy as np

def cosine_similarity(v1, v2):

dot_product = np.dot(v1, v2)

norm_v1 = np.linalg.norm(v1)

norm_v2 = np.linalg.norm(v2)

return dot_product / (norm_v1 * norm_v2)

func CosineSimilarity(v1, v2 []float64) float64 {

var dot, norm1, norm2 float64

for i := range v1 {

dot += v1[i] * v2[i]

norm1 += v1[i] * v1[i]

norm2 += v2[i] * v2[i]

}

if norm1 == 0 || norm2 == 0 {

return 0

}

return dot / (math.Sqrt(norm1) * math.Sqrt(norm2))

}

#include <vector>

#include <cmath>

double cosine_similarity(const std::vector<double>& v1, const std::vector<double>& v2) {

double dot = 0.0, norm1 = 0.0, norm2 = 0.0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < v1.size(); ++i) {

dot += v1[i] * v2[i];

norm1 += v1[i] * v1[i];

norm2 += v2[i] * v2[i];

}

if (norm1 == 0 || norm2 == 0) return 0.0;

return dot / (std::sqrt(norm1) * std::sqrt(norm2));

}

Note on Normalization: A vector is L2-normalized (unit normalized) when its length equals exactly 1. CLIP models often do this by default.

When all vectors live on the unit sphere, these metrics collapse into equivalent rankings:

- Cosine similarity becomes identical to Inner Product.

- Euclidean distance becomes a function of Inner Product: $L2^2(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = 2 - 2 \cdot \text{IP}(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})$.

This means you can often use the simpler Inner Product for calculation efficiency without changing the search results.

3. Graph-Based Indexing: HNSW#

HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) [1] is currently the industry standard for in-memory vector search. It works by constructing a multi-layered proximity graph.

The Small World Phenomenon#

A navigable small world graph has a special property: even though each node connects to only a few neighbors (low degree), the graph is structured so that you can hop between any two nodes in very few steps (empirically near $O(\log N)$ for typical data distributions).

- Intuition: Think of the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” You can connect any actor to Kevin Bacon in less than 6 steps knowing only who worked with whom.

Multi-Layered Architecture#

HNSW borrows ideas from Skip Lists (a linked list with “express lanes” that let you skip over 10, 50, or 100 items at a time). It builds a hierarchy of graph layers:

- Top Layer (Highways): Very few nodes. Long-range links. Allows you to “zoom” across the vector space quickly (like taking an Interstate highway).

- Middle Layers: More nodes. Finer granularity (like exiting to state routes).

- Bottom Layer (Layer 0): Contains every vector. Used for the final, precise search (like navigating neighborhood streets).

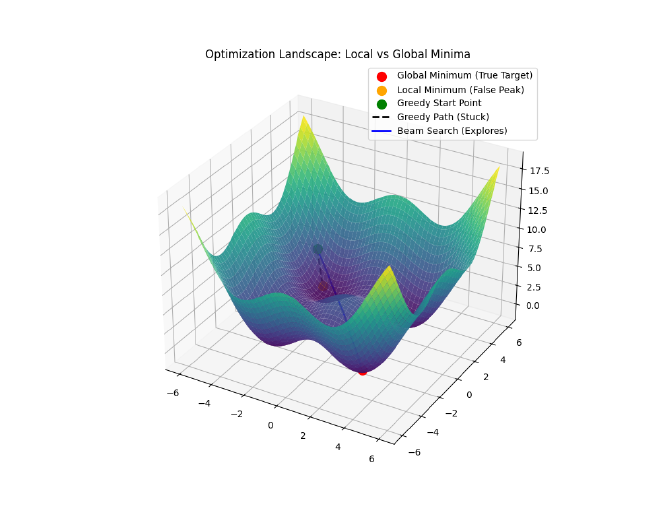

Search Algorithm (Greedy Routing & Beam Search)#

The search uses Greedy Routing with a Beam Search buffer.

- Intuition (Greedy): Imagine driving toward a mountain peak (the Query) you can see in the distance. At every intersection (Node), you turn down the road that points most directly at the peak.

- Intuition (Beam Search): Instead of sending just one car, you send a fleet of $ef$ (Exploration Factor) cars. They explore slightly different routes. If one car hits a dead end (a “local minimum” where all neighbors are further away), the others can still find the peak.

The Algorithm Steps:#

- Enter at the top layer.

- Greedily traverse to the node closest to the query.

- Descend to the next layer, using the current node as the entry point.

- Repeat until Layer 0.

- Beam Search at Layer 0:

- Maintain a priority queue

Wof sizeef(Exploration Factor). Wstores the “best candidates found so far.”- At each step, explore the neighbors of the closest candidate in

W. - Add them to

Wif they are closer than the worst candidate inW(and drop the worst one to keepWat sizeef). - Stop when no candidate in

Wyields a closer neighbor.

- Maintain a priority queue

Mathematical Complexity: Why ~$O(\log N)$?#

Why is HNSW so fast? It comes down to the probability of layer promotion, similar to a Skip List.

Rudimentary Skip List Logic (Code)#

The core idea is Probabilistic Layer Promotion. Instead of balancing a tree (restructuring the index to ensure the tree height is uniform, meaning the path from the root to any leaf node is roughly the same length), valid HNSW/Skip List logic relies on a “coin flip” to decide if a node should exist in higher layers.

import random

class SkipNode:

def __init__(self, value, level):

self.value = value

# Forward pointers for each level (0 to level)

# forward[0] is the base layer (neighbors)

# forward[N] are the express lanes

self.forward = [None] * (level + 1)

class SkipList:

def __init__(self, max_level=16, p=0.5):

self.max_level = max_level

self.p = p

self.head = SkipNode(None, max_level)

def random_level(self):

# The key to HNSW/SkipList structure:

# A coin flip determines how high up a node goes.

level = 0

while random.random() < self.p and level < self.max_level:

level += 1

return level

package main

import (

"math/rand"

)

const (

MaxLevel = 16

P = 0.5

)

type SkipNode struct {

Value int

// Forward[0] = Next node in base layer

// Forward[i] = Next node in layer i (Express Lane)

Forward []*SkipNode

}

type SkipList struct {

Head *SkipNode

}

func (sl *SkipList) RandomLevel() int {

level := 0

// Coin flip for promotion

for rand.Float32() < P && level < MaxLevel-1 {

level++

}

return level

}

#include <vector>

#include <cstdlib>

struct SkipNode {

int value;

// forward[0] is base layer, forward[i] is layer i

std::vector<SkipNode*> forward;

SkipNode(int v, int level) : value(v), forward(level + 1, nullptr) {}

};

class SkipList {

int max_level;

float p;

SkipNode* head;

public:

SkipList(int max_lvl, float prob) : max_level(max_lvl), p(prob) {

head = new SkipNode(-1, max_level);

}

int randomLevel() {

int lvl = 0;

// Bernoulli trial for layer promotion

while ((float)rand()/RAND_MAX < p && lvl < max_level) {

lvl++;

}

return lvl;

}

};

Why “Coin Flips” and Not Distance?#

You might wonder: Why use a random coin flip? Shouldn’t we pick nodes that are “far apart” to be the express hubs?

If we knew the entire dataset in advance, we could indeed pick perfectly spaced “pillars” to form the upper layers. However, that requires expensive global analysis ($O(N)$ or $O(N^2)$) and makes adding new data difficult (you’d have to shift the pillars).

Randomness is a powerful shortcut. By promoting nodes randomly:

- Distribution: We statistically guarantee that the express nodes are roughly uniformly distributed across the space, without ever calculating a single distance.

- Independence: We can insert a new node without needing to “re-balance” the rest of the graph.

- Speed: It takes $O(1)$ time to decide a node’s level, versus $O(N)$ to find the “best” position.

This is the beauty of Skip Lists and HNSW: Randomness yields structure.

Does this make search result “random”? Surprisingly, yes! Because the graph is built using random coin flips, no two HNSW index builds are exactly the same. If you index the same data twice, you will get two slightly different graphs. This means for edge cases (points equidistant to multiple neighbors), consistent search results are not guaranteed across index rebuilds. We discuss this more in Section 7: The Reality of Non-Determinism.

Let $p$ be the promotion probability, the chance that a node at Layer $L$ also participates in Layer $L+1$.

Clarification: “Existing” in multiple layers Nodes are not duplicated. “Existing in Layer $L$” simply means the node has links (neighbors) at that layer. A node at the top layer has a set of neighbors for every layer below it, acting as a multi-level hub.

Why $p \approx 1/M$ and what is $e$?

To understand why $p \approx 1/M$ is optimal, we need to balance the “width” of the search at each layer against the total “height” of the graph.

- The Goal: We want the total number of hops to be logarithmic, i.e., approximately $O(\log N)$ (empirically observed for most data distributions; worst-case can degrade toward linear).

- The Constraint: At each layer, we have on average $M$ connections. This means a single hop can traverse a “distance” proportional to the density of that layer.

If layer $L$ has $N_L$ nodes and layer $L+1$ has $N_{L+1}$ nodes, the “skip length” at layer $L+1$ is effectively $N_L / N_{L+1}$ times larger than at layer $L$. To utilize the $M$ connections most efficiently, the skip length should match the branching factor (the average number of neighbors each node connects to, $M$). This implies we want a reduction factor (the ratio by which the number of nodes decreases from one layer to the next) of $M$: $$N_{L+1} \approx \frac{N_L}{M}$$

This means the probability of a node being promoted to the next layer is simply $p = 1/M$.

Note on $M$ in practice: In HNSW implementations, $M$ is exposed as the maximum neighbor cap per layer (with layer 0 often using a larger cap, e.g., $M_0 = 2M$). The level distribution parameter $m_L$ is conceptually separate, though related via the derivation below. The user-facing knob is $M$ (neighbor cap); the framework derives the layer assignment internally.

The Role of $e$ (Natural Logarithm) The original HNSW paper implements this using an exponential distribution to determine the max level of a node: $$ \text{level} = \lfloor - \ln(\text{uniform}(0,1)) \cdot m_L \rfloor $$ where:

- $\ln$ is the natural logarithm (base $e \approx 2.718$).

- $m_L$ is a normalization factor, optimally set to $m_L = \frac{1}{\ln(M)}$.

Why does this work? Let’s check the probability $P(\text{level} \ge l)$: $$ P(\text{level} \ge l) = P\left(- \ln(x) \cdot \frac{1}{\ln(M)} \ge l\right) $$ $$ = P\left(\ln(x) \le -l \cdot \ln(M)\right) $$ $$ = P\left(x \le e^{-l \cdot \ln(M)}\right) $$ $$ = P\left(x \le (e^{\ln M})^{-l}\right) $$ $$ = M^{-l} = \left(\frac{1}{M}\right)^l $$ This precisely matches our requirement! The probability of reaching level $l$ decays by a factor of $1/M$ at each step.

Number of Layers: Since the count reduces by $M$ each time, the total height is $L \approx \log_M N$.

Complexity: Total hops = (Layers) $\times$ (Hops/Layer) $\approx \log_M N \times M$. This is very efficient for large $M$.

Total Complexity: $$ Cost = O(\log N) \times O(M) \times O(d) $$ where:

- $O(\log N)$: Number of layers in the graph

- $O(M)$: Average number of hops per layer

- $O(d)$: Cost of a single distance calculation

Key Tuning Parameters:

- $M$: Max links per node. Higher $M$ = better recall, higher memory.

- $ef_{construction}$ (Exploration Factor): “Beam width” during build. Higher = better quality graph, slower build.

- $ef_{search}$ (Exploration Factor): “Beam width” during search. Higher = better recall, slower search.

Why keep

efcandidates instead of just 1?If you only keep the single best candidate (Greedy Search), you might get stuck in a Local Minimum (a “false peak”).

- Imagine you are hiking up a mountain in thick fog. You always take the steepest step up.

- You might reach a small hill and stop, thinking you’re at the summit, because every step from there is down.

- But the real summit is across a small valley.

By keeping

efcandidates (e.g., 100), you explore multiple paths simultaneously. Even if your “best” candidate hits a false peak, one of the other 99 might skirt around the valley and find the true summit.efbuys you diversity in your search to avoid dead ends.

4. Disk-Based Indexing: DiskANN & Vamana#

To break the “RAM Wall,” Microsoft Research introduced DiskANN [2] and the Vamana graph. The goal: store the massive vector data on cheap NVMe SSDs while keeping search fast.

The Vamana Graph#

Unlike HNSW’s multi-layer structure, Vamana builds a single flat graph but essentially “bakes” the shortcuts into it. It uses $\alpha$-robust pruning to ensure angular diversity.

$\alpha$-Robust Pruning: When connecting a node $p$ to neighbors, we don’t just pick the closest ones. We pick neighbors that are close and in different directions. Rule: If a neighbor $c’$ is reachable via another neighbor $c$ that is closer, we prune $c’$. This forces edges to spread out like a compass, ensuring the graph doesn’t get stuck in local cul-de-sacs.

The SSD/RAM Split#

DiskANN splits the problem:

- RAM: Holds a compressed representation (Product Quantization) of every vector + a cache of the graph navigation points.

- SSD: Holds the full-precision vectors and the full graph adjacency lists.

During search, the system uses the compressed vectors in RAM to navigate “roughly” to the right neighborhood. Then, it issues batched random reads to the SSD to fetch full data for the most promising candidates.

Result: You can store billion-scale datasets with roughly 10% of the RAM required by HNSW, with only a small latency penalty (milliseconds vs. microseconds).

5. Partitioning: IVF (Inverted File Index)#

Index partitioning algorithms like IVF rely on clustering to divide the dataset into manageable chunks. This approach was popularized by the Faiss [4] library.

Voronoi Cells#

The algorithm runs k-means clustering to find $K$ centroids. These centroids define Voronoi cells, regions of space where every point is closer to that centroid than any other.

How It Works#

- Train: Find $K$ centroids (e.g., $K = \sqrt{N}$).

- Index: Assign every vector to its nearest centroid. Store them in an “inverted list” bucket for that centroid.

- Search:

- Compare query to the $K$ centroids.

- Select the

nprobeclosest centroids. - Scan only the vectors in those

nprobebuckets.

Trade-off: Higher nprobe = better recall but slower search.

Weakness: If a query lands near the edge of a cell, its true nearest neighbor might be just across the border in a cell you didn’t check.

6. Compression: Quantization#

To reduce memory usage further, we use Quantization. This is “lossy compression” for vectors.

Product Quantization (PQ)#

PQ splits a high-dimensional vector (e.g., 768d) into $m$ sub-vectors (e.g., 96 blocks of 8d each). It runs k-means on each sub-space to create a codebook (usually 256 centroids per sub-space, fitting in 1 byte).

- Original: 768 floats $\times$ 4 bytes = 3,072 bytes.

- PQ: 96 chunks $\times$ 1 byte = 96 bytes.

- Compression Ratio: 32x.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

def train_pq(vectors, m=96):

dim = vectors.shape[1]

sub_dim = dim // m

codebooks = []

for i in range(m):

# Extract sub-vectors for this subspace

start = i * sub_dim

end = (i + 1) * sub_dim

sub_vectors = vectors[:, start:end]

# Train k-means (256 centroids = 1 byte)

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=256)

kmeans.fit(sub_vectors)

codebooks.append(kmeans.cluster_centers_)

return codebooks

def encode_pq(vector, codebooks):

m = len(codebooks)

sub_dim = len(vector) // m

encoded = []

for i in range(m):

start = i * sub_dim

end = (i + 1) * sub_dim

sub_vec = vector[start:end]

# Find nearest centroid ID

centroids = codebooks[i]

dists = np.linalg.norm(centroids - sub_vec, axis=1)

nearest_id = np.argmin(dists)

encoded.append(nearest_id)

return encoded

// Simplified conceptual code

func TrainPQ(vectors [][]float64, m int) [][][]float64 {

// Splits vectors into m slices and runs k-means on each

// Returns m codebooks, each with 256 centroids

return trainKMeansPerSubspace(vectors, m)

}

func EncodePQ(vector []float64, codebooks [][][]float64) []byte {

m := len(codebooks)

subDim := len(vector) / m

encoded := make([]byte, m)

for i := 0; i < m; i++ {

subVec := vector[i*subDim : (i+1)*subDim]

// Find closest centroid index (0-255)

encoded[i] = findNearestCentroid(subVec, codebooks[i])

}

return encoded

}

#include <vector>

#include <cmath>

#include <algorithm>

#include <limits>

using Vector = std::vector<double>;

using Codebook = std::vector<Vector>; // 256 centroids per subspace

// Simplified conceptual structure

std::vector<uint8_t> encode_pq(const Vector& vector, const std::vector<Codebook>& codebooks) {

int m = codebooks.size();

int sub_dim = vector.size() / m;

std::vector<uint8_t> encoded;

encoded.reserve(m);

for (int i = 0; i < m; ++i) {

// Extract sub-vector

auto start = vector.begin() + (i * sub_dim);

auto end = start + sub_dim;

Vector sub_vec(start, end);

// Find nearest centroid ID (0-255)

double min_dist = std::numeric_limits<double>::max();

uint8_t best_id = 0;

for (int id = 0; id < 256; ++id) {

double dist = 0.0;

// Euclidean distance

for (int k = 0; k < sub_dim; ++k) {

double diff = sub_vec[k] - codebooks[i][id][k];

dist += diff * diff;

}

if (dist < min_dist) {

min_dist = dist;

best_id = static_cast<uint8_t>(id);

}

}

encoded.push_back(best_id);

}

return encoded;

}

The “FS” in IVF-PQFS: Fast Scan#

You might see terms like IVF-PQFS. The FS stands for Fast Scan.

- Standard PQ: Uses lookup tables. For every sub-vector code, we jump to a table in memory to fetch the pre-computed distance. This causes random memory access, which is hard for the CPU to predict and cache.

- Fast Scan (FS): Optimizes this by keeping data in CPU registers to perform massive parallel computation.

- 4-bit PQ: Standard PQ reduces each sub-vector to an 8-bit code (0-255 Centroid ID). Fast Scan uses 4-bit codes (0–15, i.e., 16 Centroid IDs). This allows packing two codes into one byte (e.g., bits 0-3 for one sub-vector, 4-7 for another), doubling the data density in memory.

- Fun Fact: In computer science, 4 bits is officially called a nybble (or nibble). It’s a play on words: half a “byte.”

- SIMD Instructions (Single Instruction, Multiple Data): These are special CPU commands (like AVX2/AVX512) that perform the same math operation on multiple numbers at once.

- Skipping the Lookup Table: In standard PQ, the code is an index into a distance table (requiring a RAM fetch). In FS, we load the distance table into the SIMD registers first. Then, we use special “shuffle/permute” instructions to compute the distance directly within the CPU register, avoiding the slow trip to fetch data from RAM.

- Result: Massive speedup because we stay in L1 cache/registers.

- Trade-off: Reduced Accuracy. Since we only use 4 bits (16 centroids) instead of 8 bits (256 centroids) to represent each subspace, the approximation is coarser. However, the speedup often allows searching more candidates (higher

nprobe), effectively creating a “recall vs. speed” win.

- 4-bit PQ: Standard PQ reduces each sub-vector to an 8-bit code (0-255 Centroid ID). Fast Scan uses 4-bit codes (0–15, i.e., 16 Centroid IDs). This allows packing two codes into one byte (e.g., bits 0-3 for one sub-vector, 4-7 for another), doubling the data density in memory.

Distance calculation uses a pre-computed lookup table, making it extremely fast.

Scalar Quantization (SQ)#

Simply converts each 32-bit float into an 8-bit integer (int8) by mapping the min/max range of each dimension.

- Reduction: 4x.

- Pros: Very fast (SIMD optimized), decent accuracy.

def scalar_quantize(vector):

# Map floats to int8 (-128 to 127)

min_val, max_val = min(vector), max(vector)

scale = 255 / (max_val - min_val)

quantized = []

for x in vector:

q = int((x - min_val) * scale) - 128

quantized.append(q)

return quantized, scale, min_val

func ScalarQuantize(vector []float64) ([]int8, float64, float64) {

minVal, maxVal := vector[0], vector[0]

for _, v := range vector {

if v < minVal {

minVal = v

}

if v > maxVal {

maxVal = v

}

}

scale := 255.0 / (maxVal - minVal)

quantized := make([]int8, len(vector))

for i, v := range vector {

q := int((v-minVal)*scale) - 128

if q > 127 { q = 127 }

if q < -128 { q = -128 }

quantized[i] = int8(q)

}

return quantized, scale, minVal

}

#include <vector>

#include <algorithm>

#include <cmath>

#include <cstdint>

struct QuantizedResult {

std::vector<int8_t> quantized;

double scale;

double min_val;

};

QuantizedResult scalar_quantize(const std::vector<double>& vector) {

double min_val = vector[0];

double max_val = vector[0];

for (double v : vector) {

if (v < min_val) min_val = v;

if (v > max_val) max_val = v;

}

double scale = 255.0 / (max_val - min_val);

std::vector<int8_t> quantized;

quantized.reserve(vector.size());

for (double v : vector) {

int q = static_cast<int>((v - min_val) * scale) - 128;

if (q > 127) q = 127;

if (q < -128) q = -128;

quantized.push_back(static_cast<int8_t>(q));

}

return {quantized, scale, min_val};

}

Binary Quantization (BQ)#

The most aggressive form. Converts every dimension to a single bit (0 or 1).

- Reduction: 32x.

- Distance: Hamming distance (XOR + PopCount), which is incredibly fast on modern CPUs.

import numpy as np

def binary_quantize(vector):

# If x > 0 return 1, else 0

return np.where(vector > 0, 1, 0).astype(np.int8)

def hamming_distance(bq1, bq2):

# XOR and count bits (popcount)

# In pure Python/Numpy this is naive;

# production systems use packed bits + CPU instructions

xor_diff = np.bitwise_xor(bq1, bq2)

return np.sum(xor_diff)

import "math/bits"

func BinaryQuantize(vector []float64) uint64 {

// Example for 64-dim vector packing into a single uint64

var mask uint64 = 0

for i, v := range vector {

if v > 0 {

mask |= (1 << i)

}

}

return mask

}

func HammingDistance(a, b uint64) int {

// XOR + PopCount (Hardware accelerated)

return bits.OnesCount64(a ^ b)

}

#include <vector>

#include <cstdint>

// Simple example packing 64 dimensions into a uint64

uint64_t binary_quantize(const std::vector<double>& vector) {

uint64_t mask = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < vector.size() && i < 64; ++i) {

if (vector[i] > 0) {

mask |= (1ULL << i);

}

}

return mask;

}

int hamming_distance(uint64_t a, uint64_t b) {

// XOR + PopCount (CPU instruction)

// GCC/Clang intrinsic for efficient population count

return __builtin_popcountll(a ^ b);

// In C++20, you can use: std::popcount(a ^ b);

}

Cons: Significant accuracy loss unless dimensions are very high. Often used with a Re-ranking step.

Anisotropic Quantization (ScaNN)#

Google’s ScaNN [3] (Scalable Nearest Neighbors) improves on PQ. Standard PQ minimizes the overall error $||\mathbf{x} - q(\mathbf{x})||^2$ (Euclidean distance). It treats error in all directions equally.

ScaNN realizes that for Maximum Inner Product Search (MIPS), only the component of the error that aligns with the query vector matters. Error perpendicular to the query barely changes the dot product.

The Trick: Since the query vector $\mathbf{q}$ is unknown at training time, ScaNN assumes that for high inner-product matches, $\mathbf{q}$ will be roughly parallel to the datapoint $\mathbf{x}$. Therefore, it heavily weighs quantization error that is parallel to $\mathbf{x}$ in the loss function, while mostly ignoring orthogonal error.

Mathematically, it minimizes the anisotropic loss. The loss function assigns a much larger weight ($w_{\parallel}$) to the parallel error than to the orthogonal error ($w_{\perp}$):

$$ \text{Loss} \approx w_{\parallel} || \mathbf{x}_{\parallel} - \tilde{\mathbf{x}}_{\parallel} ||^2 + w_{\perp} || \mathbf{x}_{\perp} - \tilde{\mathbf{x}}_{\perp} ||^2 $$

where $w_{\parallel} \gg w_{\perp}$. This forces the model to focus its “compression budget” on the direction that actually matters for dot products.

Think of it like a flashlight beam: ScaNN allows more error in the shadows (perpendicular) but strictly enforces accuracy in the beam of light (parallel). This yields higher recall for the same compression ratio.

7. The Reality of Non-Determinism#

A critical “gotcha” in vector search is that widely used ANN algorithms are non-deterministic. Running the same query twice might yield slightly different results.

Why?

- Insertion Order: In HNSW, the graph topology depends on the order data arrived.

- Concurrency: Live updates during a search can shift the graph under your feet.

- Random Initialization: k-means (for IVF/PQ) starts with random seeds.

- Floating-Point Math: SIMD instructions accumulate floating point numbers in different orders, leading to tiny rounding differences that can flip the order of two nearly-identical vectors.

Mitigations: For use cases where reproducibility is required, several strategies can be combined:

- Deterministic build seeds and fixed insertion ordering to produce identical graphs.

- Snapshotting immutable index versions so queries always run against the same graph.

- Disabling concurrent mutation during query execution.

- Deterministic BLAS/SIMD settings to eliminate floating-point accumulation order differences.

- Exact k-NN reranking on a bounded candidate set as the gold-standard fallback.

For forensic or legal use cases, an Exact k-NN fallback (brute force) on a time-bounded window of data remains the strongest guarantee.

Summary Table#

| Algorithm | Search Complexity | Typical Memory | Latency | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exact k-NN | $O(N \cdot d)$ | 100% (High) | Seconds | Ground truth, small data |

| HNSW | ~$O(\log N)$ | ~140% (100% Data + 40% Graph) | < 1 ms | Real-time, expensive |

| IVF-PQ | $O(N/K)$ | 5-10% (Low) | 1-10 ms | Balanced, large scale |

| IVF-PQFS | $O(N/K)$ (SIMD) | 2-5% (Very Low) | < 2 ms | High throughput, compressed |

| DiskANN | ~$O(\log N)$ + Disk I/O | 5% (Very Low) | 2-10 ms | Massive scale, cost-effective |

| ScaNN | Optimized IVF-PQ | 5-10% (Low) | < 5 ms | High accuracy / Google Cloud |

| SingleStore | Hybrid (HNSW / IVF) | High or Low | 1-10 ms | HTAP (SQL + Vector) |

Most modern production systems use a hybrid approach: HNSW for the hot, recent data, and DiskANN or IVF-PQ for the massive historical archive.

Diagrams generated using Mermaid.js syntax.

Note on Algorithms vs. Services:

- ScaNN is the proprietary algorithm powering Google Vertex AI Vector Search [6].

- DiskANN is used across multiple Microsoft offerings (e.g., SQL Server vector indexes [7]; Cosmos DB DiskANN features). Azure AI Search uses HNSW / exhaustive KNN for its vector indexes [8].

- Milvus supports DiskANN-based on-disk indexing (Vamana graphs) and HNSW for in-memory search [9].

- LanceDB supports IVF/PQ-style approaches today with DiskANN-related support emerging [10] (check current docs/releases for the latest).

- HNSW is the default in-memory engine for Pinecone, Milvus, and Weaviate.

- SingleStore supports IVF, IVF-PQ, and HNSW (Faiss-based), with PQ fast-scan-style optimizations depending on configuration [11] [12].

Algorithm Support by Service#

| Service | HNSW | IVF-Flat | IVF-PQ | IVF-PQFS | DiskANN | ScaNN | Flat / Brute-Force |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Vertex AI [6] | — | — | — | — | — | ✅ | — |

| Google AlloyDB [13] [14] | ✅ | ✅ | — | — | — | ✅ | ✅ |

| Google Cloud Spanner [15] [16] | — | — | — | — | — | ✅ | ✅ |

| Azure AI Search [17] | ✅ | — | — | — | — | — | ✅ |

| Azure Cosmos DB [18] | — | — | — | — | ✅ | — | ✅ |

| SQL Server [7] | — | — | — | — | ✅ | — | — |

| Milvus / Zilliz [19] [20] | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | — | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Pinecone [21] | (opaque) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Weaviate [22] | ✅ | — | — | — | — | — | ✅ |

| SingleStore [11] [23] | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | — | — | — |

| LanceDB [24] | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | — | — | — | — |

| pgvector (PostgreSQL) [25] | ✅ | ✅ | — | — | — | — | ✅ |

✅ = Supported, (opaque) = Not publicly specified, — = Not available or not documented.

hnswlib) with a brute-force buffer for small batch ingestion—they are excellent for prototyping and small-to-medium workloads but don’t expose the breadth of indexing strategies seen above. Similarly, Faiss is a library, not a managed service—it supports nearly every algorithm in this table (HNSW, IVF-Flat, IVF-PQ, IVF-PQFS, Flat) and is the engine behind several services listed here (e.g., SingleStore, Milvus).8. References#

- Malkov, Y. A., & Yashunin, D. A. (2018). Efficient and robust approximate nearest neighbor search using Hierarchical Navigable Small World graphs. IEEE TPAMI. ↩

- Subramanya, S. J., et al. (2019). DiskANN: Fast Accurate Billion-point Nearest Neighbor Search on a Single Node. NeurIPS. ↩

- Guo, R., et al. (2020). Accelerating Large-Scale Inference with Anisotropic Vector Quantization (ScaNN). ICML. ↩

- Johnson, J., et al. (2019). Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs (Faiss). IEEE Big Data. ↩

- Aggarwal, C. C., Hinneburg, A., & Keim, D. A. (2001). On the Surprising Behavior of Distance Metrics in High Dimensional Space. ICDX. ↩

- Google Cloud. Vector Search overview | Vertex AI. ↩

- Microsoft. Vector Search & Vector Index - SQL Server. ↩

- Microsoft. Vector indexes in Azure AI Search. ↩

- Milvus. On-disk Index | Milvus Documentation. ↩

- LanceDB. Add LanceDB to ANN benchmarks · Issue #220. GitHub. ↩

- SingleStore. Announcing SingleStore Indexed ANN Vector Search. ↩

- SingleStore. Tuning Vector Indexes and Queries. ↩

- Google Cloud. Create an IVFFlat index | AlloyDB for PostgreSQL. ↩

- Google Cloud. ScaNN for AlloyDB: How it compares to pgvector HNSW. ↩

- Google Cloud. Create and manage vector indexes | Spanner. ↩

- Google Cloud. Perform vector similarity search in Spanner by finding the K-nearest neighbors. ↩

- Microsoft. Create a Vector Index - Azure AI Search. ↩

- Microsoft. Vector search in Azure Cosmos DB for NoSQL. ↩

- Milvus. In-memory Index | Milvus Documentation. ↩

- Milvus. Index Vector Fields | Milvus Documentation. ↩

- Pinecone. Nearest Neighbor Indexes for Similarity Search. ↩

- Weaviate. Vector index | Weaviate Documentation. ↩

- SingleStore. Vector Indexing | SingleStore Documentation. ↩

- LanceDB. Vector Indexes | LanceDB Documentation. ↩

- pgvector. pgvector: Open-source vector similarity search for PostgreSQL. GitHub. ↩